In the Heart of a Minority

/Charles Nilon

Professor of Urban Wildlife Management

University of Missouri

Charlie really showed me that as a faculty member, it is a safe place to talk about the challenges, down to the details of being a minority in Ecology. I sat down with him, just like the previous interviewees, and caught up with him after having that first deep discussion four years ago.

What we talked about in this interview brought us back to that safe conversation space. Not only does his life experience speak to what he’s lived in his heart, but his place at the University of Missouri puts him in the thick of “A” minority experience. If it was anything that I learned from him it’s this; that his story and words lead my heart to better understand what might be happening in other places of the country where the diversity of communities looks much more different than what I’m exposed to here in the Bay Area. Take for instance the statistic he provides; for a campus (University of Missouri) with a faculty population of 3-4,000 (much like UC Berkeley or UCLA), less than 1% were minorities for a long time. Today, Charlie is one of two faculty of color in his department.

He’s an inspiration to me in the ways in which he has motivated himself to succeed as well as how elegantly he’s played that important role of working with colleagues that may have different perspectives than him and especially what his students have brought to the table.

RR: The last time I spoke to you was about 4 years ago. Are you still at MU and in the same capacity?

CN: Yes, I’m still here at the MU campus in Columbia and I’m halfway through my 24rd year here! I started June of ’89. In fact I interviewed here 25 years ago this week. So I’ve been here a while. Things are going well here, I think the things career-wise with research, teaching and things like that are going well. I think the issues of being faculty at UM… there will always be challenges there, in terms of the setting.

RR: How did you get interested in Urban Ecology going back to even your younger years and where did your inspiration came from?

CN: I grew up in Boulder, Colorado. Born and raised there. Growing up I did outdoor things. My dad would take me fishing, walking, hiking. We watched animals, walked up creeks. So I did that kind of stuff growing up. And I was also a Boy Scout. So I was always interested in the outdoors.

What was funny was, I never connected that interest with anything beyond just liking the outdoors, like

getting a job. When I was in high school and elementary school I don’t think I ever thought about that for a career. Interestingly enough, my outdoor experience was always kind of urban/suburban. Growing up in Colorado we went up to the mountains, but most of the real contact I had with nature and hands on contact was in an urban setting. We used to go looking for turtles along the creeks in town and I had a friend who lived across the street from me. He had a teacher who taught him about birds in 3rd or 4th grade. So we looked around the school for birds in this place between 2 neighborhoods.

Then when I went to college at Morehouse College in Atlanta, I was a Biology major. I liked science but I had no experience looking at Ecology as something you do. When I got there I thought I wanted to be Pre-Med. But after a year I liked science. I didn’t want to go to medical school and my advisor at Morehouse suggested I volunteer somewhere.

My dad was an English professor at the University of Colorado so I grew up in an academic household. He helped connected me to Jan Linhart in the Biology Department who was a Forest Geneticist. They were looking at bark beetles on Ponderosa Pine right on the front-range. So I volunteered with him one summer to collect pollen samples. And I don’t think I did a particularly good job, but I volunteered and spent a couple of days a week in his lab. While doing that, I made contact with a graduate student who had been a Wildlife major as an undergraduate. For the next couple of years I thought about that as a career. And that’s how I came into Ecology and Conservation.

Now the urban part came about this way: I’ve always liked cities. My family was the only one in our family living out in the West. On vacation we’d always go to Alabama or the East Coast so we always went to big cities. When I got to graduate school (Yale School of Forestry) and started working on my master’s degree, I started thinking about the interest I had in cities. And I became interested in linking my interest in nature with my interest in cities. For my MS, I worked on a project suggested by a faculty member, where a graduate student wanted to look at wildlife in New Haven. I got involved in doing that for a master’s project. We went out to different neighborhoods of New Haven and trying to look at what species were there. So from the time I started my MS to now, it’s just expanded.

It really came from having an interest growing up, exposure to outdoors growing up and being exposed to the city.

I was at Yale for an MS, worked for 2 years for Missouri Department of Conservation. I started in a temporary wildlife biologist position that became full time. I went back to get a PhD at State University of NY in Environmental Science and Forestry. That was on an urban wildlife project. My advisor was Larry VanDruff, who started a lot of the urban wildlife research that was carried out at US universities. While I was a graduate student I was a coop student with the USDA Forest Service Northeastern Forest Experiment Station on their urban exposure to wildlife ecology and urban ecology.

RR: You grew up in Colorado until college and found a home in Missouri through professorship.

CN: And this is pretty much home now.

RR: In the context of time, you went to grad school and figured out your pathway. What was the landscape of Urban Ecology like then? Was it a new and upcoming concept or had it been there for a while? I ask because I see that a lot of the times urban environments are kept very separate from what natural sciences regards as “environment”.

CN: When I went to Yale, there were three faculty members who where interested in urban areas. Steve Berwick, a Wildlife Ecologist, and Bill Burch, and Stephen Keller who were both Social Scientists. The person I did a project with at Yale was interested in the wildlife side of Urban Ecology. I think he had a legitimate interest in urban areas, but I don’t think he saw this as a core part of what his work was. When I got to my PhD, Urban Ecology was viewed very differently.

SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry had several faculty interested in urban ecology. They viewed it as a big, organized discipline that goes back to the 50’s and 60’s in Europe and in Asia, then continued in the US beyond that. I'm a Wildlife Ecologist. Urban wildlife is a subfield of Wildlife Conservation that at least goes back into the mid-70’s. So, when I was in graduate school (MS) in 1978, by the time I started, Urban Wildlife Ecology was well underway.

I think that wen i was in grad school most ecologists viewed urban ecology as viewed by most ecologists as a separate from mainstream ecology. It was viewed as very, very applied and not really relevant to any Ecology. To give an example of that, Wayne Zipperer and I were in graduate school together at SUNY. ESA was in Syracuse that year and we led an urban ecology field trip. That was the first urban ecology field trip ever done with ESA.

RR: After working at Stanford I moved onto working in the non-profit sector in the Bayview neighborhood of San Francisco. The environmental justice issues were “in your face” and surrounding us everywhere. To me, that is urban ecology as well. But a very strong component of environmental justice is how society plays a part in how we see the environment. Do you find that, because environmental justice is so clear with pure data, that there are connections to race and economic classes to our land use? And how similar or different is that kind of lens to what you do in Urban Ecology as a discipline?

CN: I would say that with my research has a very strong environmental justice focus, but that’s really just developed in the last 15 years. Some of the delay was coming from a tradition in ecology that there’s the value of science as being objective, and this objective where environmental justice was just advocacy. And from my experience, I’d see these things, but never quite related the justice issues to what I did. I say. Once I got to MU and started taking on research projects I started to see the links between my research and environmental justice. Leanne Jablonski and George Middendorf have been a big influence on me in this area.

When I was at SUNY a faculty member in the forestry department studied vegetation in yards across the city of Syracuse. And the thing that stood out of the study was how much of a justice component there was to that low income African American and Puerto Rican neighborhoods were different than other neighborhoods, and upper income neighborhoods. I was thinking about that in graduate school and after I finished, that definitely influenced me a lot more. So now the environmental justice lens is really a big part of what I work on. A lot of the research that I do I try to intentionally look at neighborhoods focused on the nner city and try to understand people’s day to day interactions with nature and how that shapes the Ecology of cities. So that’s one thing I’m interested in.

RR: So, you growing up in Colorado I know that there’s a very, very low percentage of African Americans here. Did your upbringing influence any of that work you do in environmental justice and do you go back finding yourself connecting to you being a minority in Colorado?

CN: Yes, definitely a couple ways. One thing that my dad was interested in was history. And I used to get

my hair cut by this guy in Denver, named Paul Steward. He was a barber who started this Museum called the History of the Black West. We’d go over there and talk to him and see all these pictures. He would talk to all these people in the community that grew up in Colorado. They would talk about going to “Red Rocks” or these other places outdoors. Even though I grew up where there weren’t many black people, I grew up knowing that there was a connection with nature and people doing things outdoors. I didn’t see that being involved with natural as something unusual.

When I went to Morehouse, an HBCU in Atlanta, that was the first time I experienced being around a lot of black folks that didn’t really get into nature. And it was interesting to experience that at Morehouse where most students were pre-med majors.

A role model for me was Ted Washington, a wildlife biologist with the Colorado Division of Wildlife. He had gone to Colorado State University. I met him during graduate school and I saw myself doing that kind of work. Steven Keller is a Social Scientist who did a lot of human dimension stuff. When I was in his class it was interesting because he went through a lot of literature and did a lot of research about attitudes towards nature. A lot of research said, "Black Americans have negative attitudes towards nature”. And I remember being in his class and thinking, okay, I get what he’s saying on the one hand, but I think there’s something missing about what he’s saying.

RR: The statement that Keller made about Black Americans having negative attitudes towards nature... When you said there was something missing in that statement, what did you mean by that?

CN: A lot of the ideas that people in conservation and in ecology view engagement with nature very much through their own lens. So, they say, okay, “you’re interested in conservation, that means you spend money to join the Sierra Club”. They have an image of what that person’s going to be like. People might be engaged in nature in other ways, for example Judith Li at Oregon State University's Fisheries and Wildlife Dept. wrote a book, To Harvest, To Hunt. What she was saying was that when biologists talked about what people fished for or how they interact with nature, the model was always from people in the recreational lens. They don’t think about the fact that say, people particularly from China, eat different kinds of fish. So when the Chinese came to San Francisco, they ate different kinds of fish. They would fish for different kinds of things. So there's that mainstream model of saying, “Here’ s what you do if you fish”; the idea that everyone’s experience with nature is uniform. It results in people assuming you are alienated from nature or want to be separate from nature. Questions are often asked in a certain way to have this outcome.

I think about gardening. My own family like my dad’s cousins from rural Alabama (more rural folks) liked to hunt. They gardened, hunted, and did all those kinds of things. I think if you asked them about their views on ecology and nature and all that, they probably wouldn’t say a whole lot, but if you ask them about the things they do, they do a lot of different things outside. So I got interested in those kinds of things, like how do people interact with nature. What Judy did in this book, was talk to some people in Portland and surrounding areas to talk about what their experience with nature. She was trying to see "What was your experience?’ instead of saying, like those in academia would tend to say "Your experience should be this".

RR: It reminds me a lot of how I would communicate to youth or sometimes in my presentations about the environment. Everyone has his or her own definition of what the “environment” is. And it might not necessarily be what the larger group says it is and there’s always going to be value in different definitions of "environment”. That’s not to say that any of these definitions are invalid, but it kind of plays out that way in our world. That’s where I see some of this conversation about diversity because the majority of folks come from one perspective on defining these things, like what "Ecology" is, what "environment" is, what "successful careers" are. Then the challenge is, while we recognize there’s the minority voice that hasn’t been heard loud enough yet to make that included in the norms and conversations, how do we reach a point where it’s a shared movement towards continuing the work. Because there’s a lot of, “they see it this way” and “we see it that way”.

CN: We can look at ESA and what SEEDS has done for the organization. In some ways, maybe not so much the perspective of the students of SEEDS, but I think SEEDS has changed the culture in two ways. (1) If you go to ESA now, versus going to ESA 20 years ago, its completely different, the people look different (2) SEEDS brought in students and faculty who have different ways of looking at ecology they’re all Ecologists.

ESA has always struggled with this idea that you’re only a real ecologist if you get a PhD and you’re at a university teaching. One thing that SEEDS has done and something you are doing with this project, is saying that people have all these different pathways they take and saying that most people who belong to ESA aren’t traditional Ecologists. That’s one thing I always remind myself of is that majority of the membership aren’t necessarily big people doing research at a big university. There’s a diversity there of community colleges, agencies, consultants, people who do outreach. So that vision of what people are is a lot more diverse then we often think.

RR: I think there is progress there in the way our world is moving towards a more diverse atmosphere and make up of folks. It’s inevitable that it’s going to have to progress with that and hopefully it will be in the time frame that is beneficial for ESA as an organization to change perspectives.

CN: I think that where Ecologists struggle a lot is in that notion that “no one cares about what we do”. Ecologists understand the issues that people really deal with in their lives, and they see how Ecology relates to that. Like when you talk about what’s going on in Hunter’s Point in San Francisco, there are a lot of issues going on there. People recognize that there are a lot of things going on there.

One of the issues we talk about in my classes is talking about pollution, or exposure to lead contamination. We talk about St. Louis and the Missouri River. We have a lot of lead contamination risk with lead-based paint and over-housing, and that’s an ecological issue. There’s a social issue as well, but understanding how lead works as an element and how it cycles is an ecological question. So understanding how you get exposed to lead is something an Ecologist would be involved with. I think that idea when you engage communities, working with residence, raising issues, those are things that can bring things together. Because seeing that there are diverse perspectives of what Ecology means between two people is really important.

RR: Your location now and your experience…What are the demographics of your area?

CN: Missouri is a Midwestern state has 2 big cities St. Louis and Kansas City (2-3 million person metro cities). There are 4-5 cities in the 150-200K population range like Columbia, Springfield, and Independence. Missouri has 10-12% African Americans and a small Latino population in Kansas City, and immigrants from all over. There's a very small Asian, primarily Chinese American population. And St. Louis has the largest Bosnian population in the US.

Columbia mimics the state in demographics. There are lots of people who have lived here for a long time, several generations. The university’s main campus (Columbus) out of 4 other campuses, is the main research and teaching location with 35,000 students. Until the 1950’s MU did not admit black students. The first black student in the 50’s, they hired their first black faculty member in 1975. The overall number of faculty of color, US born, is under 50.

RR: What’s the total number of faculty on campus?

CN: 3,000-4,000 faculty, similar to what Berkeley or UCLA has. The minority faculty was under 1% for a long time. Before coming to MU I was working as the urban wildlife program coordinator for the Kansas Department of Wildlife and Parks. I was encouraged to apply for the job by the Department Chair, who I knew.

If I were to generalize the experience of most faculty of color at MU, in some departments minority faculty have been really successful. They’ve had really successful careers. I think that in other departments other people have had really difficult times. Some of this may be do to the culture of the department, but very much an individual experience.

I'm in the School of Natural Resources. It has roughly 40 faculty members. I was the first Black/minority person hired.A black woman was hired just after me, received tenure, and let about 10 years ago.

In terms of the research, as I’ve include more of the environmental justice components to my research, my graduate students have been much more diverse than most other faculty in my department. My students say that a lot of other grad students would ask “Why are you interested in that, why are you studying that?” And it’s been an interesting experience for my white students who have also been asked why they are interested in environmental justice.

RR: So it’s like a default to question why you’re there instead of accepting it as just another topic.

CN: And I think it’s changed. In general I like my experience, and I like the people. I think some of my frustration is from being here a long time and seeing that there are some things that change and some things that don’t. It’s this frustration that people SAY diversity is important, but they don’t seem to recognize the things which help to make our department more diverse.

RR: It just doesn’t seem like a norm that people even think about the importance or impact of what it might be to have a more diverse workspace. And so it’s never put in the front of anyone’s efforts. It’s just kind of on the side... over here. That’s a very common frustration that I’ve experienced working with diversity programs on a deeper level. There’s good intention there, but there’s no knowledge of what to do with the information from the people.

So your student did a thesis on this. What happened to the information that she gathered? Is anyone using it now and how is it being implemented?

CN: I'll give you an example, Lianne Hibbert was on of my grad students who did an evaluation of the first cohort of SEEDS students. Remember that the first cohort of SEEDS students all came from HBCU institutions. There were two parts to the program. Campus SEEDS chapters were important to students because they provided a support network. SEEDS also did a lot of work with faculty members at the SEEDS institutions with the idea that if faculty were engaged they would engage students. The faculty development part of SEEDS was not continued.

Lianne found that what really got students motivated was the community component and justice component. She said that “our campus did something with our communities” and that was something she found on all campuses all across the board for all the schools. That was something that developed independently from anything that was initially planned. So students said that they wanted to do something that would really get them involved with communities.

The bigger part of your question is…I think that the people who ran SEEDS at that time recognized what she did, and they also recognized some of the results of what Alan Berkowitz (who started SEEDS) did. I think that recognition is reflected in SEEDS emphasizing campus chapters. On the other hand, I think that SEEDS had a harder time understanding the bigger picture of what went on at HBCU institutions, particularly the role of faculty mentors. And I think that at times ESA as an entity struggles with the idea that there is "A" minority experience and forgets that students of color are a very diverse group.

RR: Well, it almost sounds like they know what “a minority” is, but they don’t know what diversity is.

CN: Yes, that’s what I was getting at. They’re missing that piece.

RR: Yes, that was a common frustration with my peers because some of us recognized this missing piece. When I first started, this community was like heaven! I needed it. And it just kind of fizzled out when we started graduate school. We recognized their strategies of engagement and community building and we wanted to keep that there. But ESA as an organization limited their focus in where they wanted to bring those opportunities; only undergraduates. Especially the I grew close to. We wanted to keep these things going and voice ourselves and participate more with SEEDS. But because they limited their outreach strategies, some of us didn’t really see that as relevant for us as graduate students.

I actually worked really hard on it for 2 years and convened a cohort of alumni to get excited about SNAP (SEEDS Network for Alumni and Professionals). And I think alums are continually excited when they hear about it, but what I found is that I got burnt out from it because of what you said before. They recognize that there are things that are beneficial to diversity, but don’t quite know what to do with that information. So I was left with an alumni group that was all volunteer run. I mean the point is to keep that pipeline and pathway continued on into professionalism and not keep the effort in only getting undergraduates engaged. The point of even pitching this to SEEDS and saying, “Please invest in this area and let’s work together to try and find resources to do this. But it was a response like, “Yes! This is all good and great, we’re cheering on the graduate students, but we just don’t know what to do with you guys.” And I feel like, really? We’re screaming for help!

CN: That raises a good point because one of the things we talked about was about that very first cohort. A bunch of us were impressed that, WOW, there were PhD’s that came out of this!

I should mention that in addition to her masters degree, Lianne was hired to assist in in depth interviews of all the first SEEDS cohort. That first cohort was 40 people. They would have started in 1997 and by the time Lian interviewed them in 2002, everyone was still involved in Ecology in some way. But ESA was questioning whether SEEDS was effective in their efforts because they weren’t getting enough PhD candidates from the program.

The first cohort included people of very diverse outcomes and careers that benefitted from SEEDS. There were Masters students with jobs at state agencies, medical students that were interested in public health because of SEEDS, etc…but ESA was questioning whether this really addressed diversity. For example, if someone was in SEEDS and becomes a doctor or a high school teacher and both really address environmental issues, is this a success?

The big questions still is... What does diversity actually mean and what does it mean to actually have a field that’s more diverse?

RR: There’s also something to be said about increasing numbers and participation. But in real life you’re going to have to interact with people and realize the context of diversify the field you’re in. What can you say, from your personal experience, how to navigate that in a healthy and constructive way? Like you are now are still one of very few in your institution, people of color. In the day to day, what does that mean?

CN: What I’ve found is that, you lead multiple lives and there are multiple things you do. I recognized early on that in anything, in order to be effective you have to do the things you are expected to do as part of your job. So at the university it’s about teaching, research and services, that’s what your paid to do and that’s where you’re evaluated on. I understand that you have to be able to show that you’re doing that. And that’s part of what drives me to do the work. I try to think about how diversity works to uplift my teaching, research, and services. I’ve tried to look at what my interests are, what are important things to me, and how I can incorporate that in the things I do. For example, I was really worried at first about doing work related to justice issues, that it would be really, really different. But I found if I showed that as being a part of my teaching, research, and service it helped me navigate through.

My perspective has always been in first recognizing that I have a right to be at this university. I’m part of the MU and my experience isn’t of just a minority at UM, but that I’m part of UM and its culture and its changes. Second, I’ve tried to look at it as what I bring to my department, how that strengthens the department. I’m interested in broadening it and making it a different place. So those are two things I try to look at.

RR: That’s your motivation and something you remind your students of. Have you ever experienced that inspiration? Have you experienced a time where a student of color has been inspired by just seeing YOU as their instructor?

CN: Yeah, I have seen that and it’s kind of strange. Like Tommy Parker, he was my PhD student when I was at the University of Louisville. We used to talk about his experience. It is inspiring for me to see that I have been able to see that I impact people’s experience. I recognize that you do serve as a sort of a motivator. Ted Washington who is in Colorado in the Forest Service while I was in graduate school, Bob Williamson who was at Tuskegee University working with the Forest Service. Knowing that these guys were my motivators and to say there are these guys that I might have talked to once and told me, “Yes you can do this, so man, here are some of the scrapes I had along the way…”

RR: Have you had any experiences where in your work and support of students, has the context of having a discussion about diversity been challenged by your department?

CN: I think it has come up in different ways, but I try to be outspoken about diversity in the department. I really saw this come up when more students of color came to the department. When two graduate students were working on their PhD’s, both of them had a particularly difficult time with faculty members who they felt challenged everything about their experience; their dedication, intellect, everything they did. I don't think that the professor was doing this intentionally, but I think that the students perceived that they were being singled out and that their perspectives on their experiences as students of color in our department were being dismissed.

So, I’ve had to speak in that way. What I’ve seen in my department is that our faculty is still trying to figure out what diversity means. Like, they can’t quite “get” who people are. But my role here is really to say, “Okay, just like majority students they come with all these different backgrounds. You have to recognize that with minorities you have this diversity too and what they might bring with their experiences.”

RR: It just becomes this awkward social interaction when you ask what the ethnicity of this student is, or these other questions to get to know someone. You have to be so careful not to offend anyone.

RR: Last things you want to mention?

CN: Well, I think it’s really exciting and really interesting to do this interview! And I’m always interested in this whole diversity thing and how fields change and how it happens over time. It’ll be interested in what you get, who you interview.

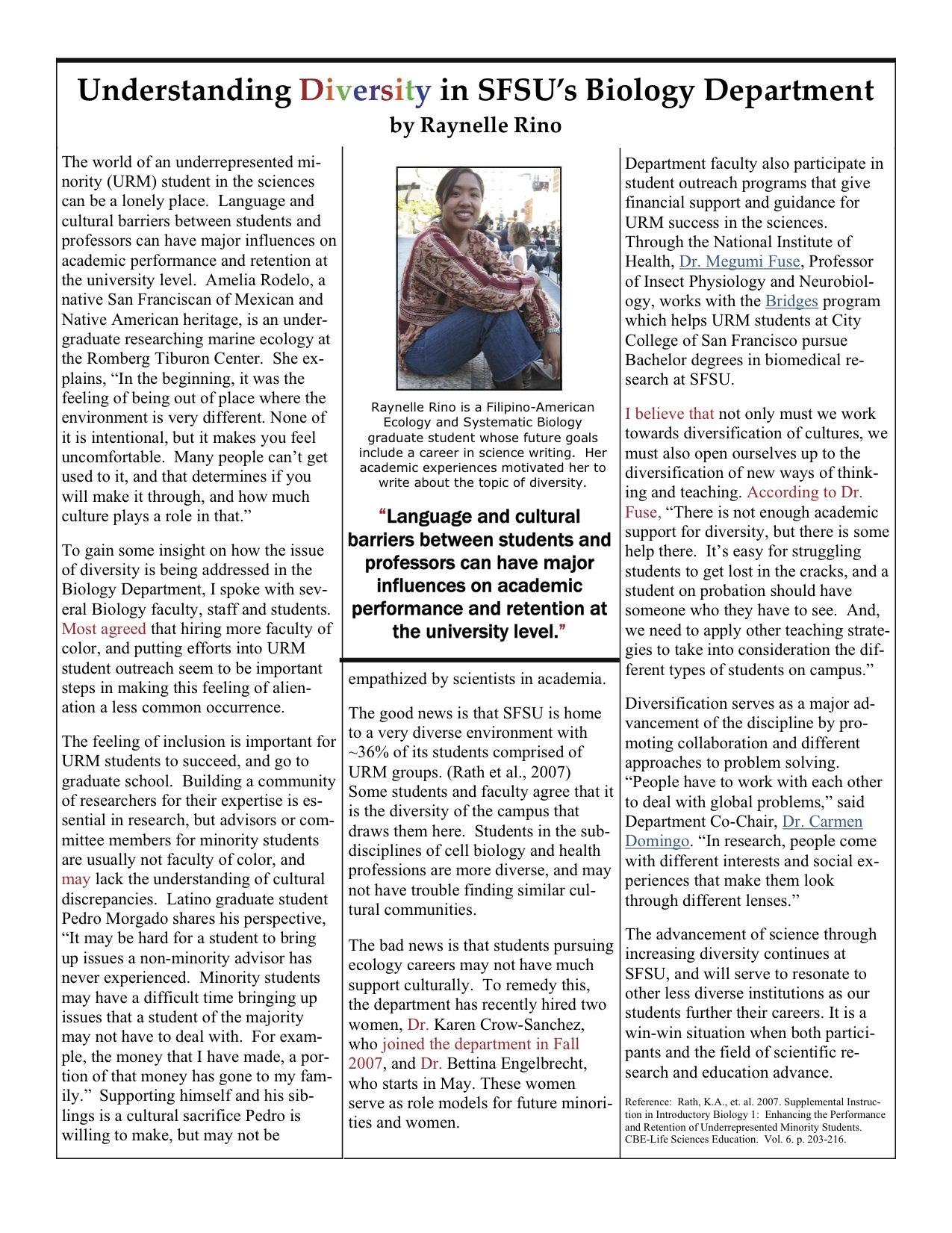

To end this year, I decided to share a piece of writing I did back when I started graduate school at San Francisco State University. I started my program in 2006. I’m still struggling to finish. In retrospect, I read back on this piece and reflected on where my life was at that point. And where I am today with respect to this conversation about diversity.

To end this year, I decided to share a piece of writing I did back when I started graduate school at San Francisco State University. I started my program in 2006. I’m still struggling to finish. In retrospect, I read back on this piece and reflected on where my life was at that point. And where I am today with respect to this conversation about diversity.