Yasmin Lucero

Senior Statistician, Gravity.com

It’s always a great feeling when things come together naturally. When I met Yasmin I didn’t know her, anyone she knew, or even what area of Ecology she was working in. I was simply scouting for Ecologists during a conference to talk diversity with me. Although I vaguely remember, I know she was sitting in on an event and after hearing that I was interested in capturing interviews with like-minded folks, Yasmin gracefully agreed to spend a few minutes with me outside.

It was real, true to the heart, and very emotional. I remember her crying as the conversation brought up thoughts about her mother who had passed recently. Initially, I felt bad that my questions provoked some sadness, but it also helped me understand her openness and her kind heart. I gained a lot from sitting down with her for only a few moments.

Four years later I reached out again. I wanted to talk deeper about diversity and capture her story for this blog. Our conversation may leave you surprised a few times, maybe even disheartened, but I’m certain you’ll see that the “big decision” she made comes straight from her core of happiness.

The first surprise was learning that as we began our phone conversation, Yasmin was just coming out of a job interview in good faith that she was actually hired! We caught up a bit and began casually discussing the purpose of The D Word and this idea that people need a “safe space” to talk about their challenges. This was our first line of attack. And so we proceed….

YL: I just want to say that there are a few reasons why those conversations aren’t happening. It’s that very few people are in the position where they have someone to have that conversation with. I think that issue with Ecology and diversity is that the core of the issue in general, is that people are isolated around others who just can’t have that conversation with them.

RR: Yes, and that’s a point I want to make. Often times we don’t have a safe space to do that, and that feeling of safety will take us to that critical point. But it has to be there.

Let’s start with who you are. Can you describe who Yasmin is and how you got started in this field and what you’re doing now?

YL: Well, I got into Ecology pretty young. In high school I was involved in an alternative program that was very engaging for me. This was a program where a speaker was leading it and teaching us the biology of salmon. But structurally it was really open-ended and independent where students were able to just design their own study to make our own thing happen. And that was really good for me. And so I was really engaged and deeply involved in this project and it happened to be about STEM and biology. It got me into field of Ecology and I went off to study it. So that’s how I began.

I did my undergrad in a very Ecology focused program, then went to grad school in Ecology and spent 4 yrs as a Post Doc in the same field. Recently (in the last 2 years) I decided that I needed to change my field and move out.

So for the two and a half years that I was a Post Doc, I was working for NOAA, my husband was working in LA and I was in Seattle and we were commuting back and forth. That got really old and I just decided to move down to LA and I transitioned into consulting. I was working from home in LA and took a sabbatical for myself to think about what I wanted to do and what next move I wanted to make. At that time I had a baby and took a long maternity leave. And I’m just now (my daughter is 11 months) am at that comfort where I’ve taken a break, figured things out, did some retooling of my skill sets, started applying for jobs, and it looks like today, I now found my job!

Actually it looks like my job search has gone remarkably well! This is completely different; it’s totally outside the realm of Ecology. It’s a tech company that does recommender engine space. You know when you go to Amazon and they say, “if you bought this, then you’d love this”…So people who come up with those recommendations, that’s what this company does. They have a role that really is a nice match for me. I’ve had 3 different distinct job opportunities, and this is the one I’m choosing. Part of it is because they are really jazzed about my background and the research I’ve done and the system that I’ve worked in. They think that that’s a great perspective to bring to this problem that they have of ‘searches’.

RR: So they saw that you coming from the scientific, Ecology realm was a value that can be brought to the company that doesn’t necessarily focus on Ecology studies? So it’s also like social media as well because it’s based on recommendations?

YL: Yes, this particular company is all former people from a big tech company. Kind of like, the best people from that company came together to create this recommender engine company. Which is actually a good pedigree, it’s a good group of people.

RR: It’s nice to hear that people are thinking in that way and I feel like that’s the direction of people’s thinking on innovation and how to hire people. Like, you have to understand that if someone had a specialty somewhere else, it doesn’t mean that they don’t have value in a realm that may not seem relevant. But gaining perspective from different angles has actually driven a lot of good collaboration and thinking outside of the box. This period of time that we are in, there is so much that has moved so quickly with social media and that kind of interaction and workspace. Some people have figured it out, or are in the middle of figuring it out... That there’s are different way to work these days and there are different opportunities, and to grab those. So I guess where I’m going with the conversation is, from your experience, when you say this is a perfect fit for you, what does that exactly mean in the context of coming from a rigorous scientific background to something like a recommender company that you’re at now?

YL: When you have a research career like I did---I have a PhD and a Post Doc---I have many, many, many years invested in that problem space. And the decision to leave it behind is an extremely difficult one. Because there’s a tremendous amount of domain knowledge I have that is now just, well… used to be really important and now is just…abandoned. It’s a very painful process to decide that all these things that you had worked for and studied for, you’re going to walk away from that and focus on an area where you don’t have that strength; you’re a back stand novice. It’s that feeling that you’re throwing away your training. I don’t believe that’s what’s happening, but it very much feels that way. I think that what you’ve done very much informs what you will do and how you do it. And it’s not always predictable what shape it’s going to take. Yes, there are specific citations I won’t have to keep in my memory anymore because I’m not ever going to cite that paper again. But Its difficult to predict the way your knowledge and expertise and contributions are going to be relevant in the future. Like, its difficult to project forward. I think in every step you just have to look at where you are now and do what is best at the moment and try and not project too far into the future or worry about it because you just don’t know.

And the decision to walk away from Ecology, there were certain pain points. There had been pain points, more or less, throughout my career in Ecology, but they were just getting worse instead of better. And I reached a point where I just needed to move on. A lot of it was the culture that I was encountering just wasn’t as open to change or innovation that I felt it needed to be. Particularly, given that it’s “science”.

And that was on the subject that I left, it was also on the social level. I felt like the community I was in was very, very narrow and I just wasn’t… (It was one of those groups of people that couldn’t’ fathom somebody who just had a different experience than them.) And it really did leave me feeling very invisible in a lot of ways because there were a lot of things about my experience that couldn’t be discussed.

I wasn’t in front of people I was relating to. And that’s important; this is your life, you work hard, you work long hours, you spend a lot of time with these people. If you don’t relate to them, then it’s just kind of weird. For me, it took this form of “Seattle vs. LA”. I was spending half time in LA, half time in Seattle. LA was ethnically like the place I grew up and Seattle… is Seattle. There’s this thing called the “Seattle Freeze” because people in Seattle are notoriously just not very friendly. They’re not interested in meeting new people or reaching out. Some of that is just the experience of being in the city, but that was my experience.

I was at this job for 3 yrs, I got along well with coworkers, they were friendly, but never did anyone really invite me to their house for dinner or anything like that. I would invite them occasionally to my home and none of my coworkers came. I have a lot of great friends in Seattle, but no one I worked with ever came to my home. And I was really ill suited to host anything having a studio apt, I was gone half the time. But I was the only person who tried to make any real interaction happen on any level.

So it wasn’t a really happy place for me. And I was in a place in Seattle, where I could have stayed there indefinitely. I could have stayed doing what I was doing. It was a cushy, comfortable, government role that I could do forever. So I had to make this difficult decision to walk away from the security and take risks and put my life on a different path.

RR: I can relate to that “not relating to the culture” in the day to day. Maybe if you can describe more in depth what that means, when you say you weren’t particularly comfortable, or didn’t really form those friendships or interactions with coworkers. What happened there and what do you think was going on?

YL: Typically, there was a particular group of people I was involved with. What they would do is they would go white water rafting, biking events, outdoor stuff that I wasn’t particularly involved with. So when gathering was happening, that’s what was happening and it was the only way people were engaging. They’d go skiing together sometimes.

Also, and this is more to the point: that particular institution (NOAA) had a relationship between University of Washington and the NOAA lab there. Almost everyone working in NOAA lab had come from UW. So many of them had formed their relationships a long, long time ago, came to grad school and formed this click. By the time Post Doc came around they became very busy and their lives were very full. And even being as connected as I am, I really didn’t feel like an outsider. But coming from the NOAA lab in Santa Cruz was enough of an outsider status that it wasn’t a nice space there.

In the context of when groups form, incidents of social grouping and the fact that I was the odd one out…there was also a cultural factor there and that was what bothered me more. I felt like, that all makes sense to me, the cultural factor, but you have to overcome that. And I think it’s a value I have that I can never really accept the fact that they weren’t just like that. I don’t know what the mind set is, but I don’t like it. You have to have parties, and you have to make it happen!

Also, being in California, even in the relatively shallow way that I was, it made me realize that that was happening a lot more. My sort of default instinct about the way things should go down was much more likely to happen. I just realize that I didn’t want to compromise at that point and I wanted to be around other people who had the same attitude about socializing and putting energy into having that life.

RR: So did you also have the feelings of just not really connecting?

YL: Oh yes, there was definitely problems of not really connecting and it came from just not having the opportunities to connect. And there are a lot of reasons why it was showing as difficult, but there just wasn’t anything to counter that. There are always reasons not to connect. But you want to cultivate an environment were relationships are being built. These people were very, very nice, but you couldn’t really talk about “things”. More importantly, it’s not just about the social happiness factor. It really impeded our work and made it impossible to work together.

One particular example, I had a collaboration with my lab mates and ultimately the collaboration just imploded. Because we could never get on the same page. And this is a point of cultural mismatch. We were on the same page very specifically on how to do the analysis. We had the data and we had to decide how we were going to attack the data and why and what questions we were going to prioritize. So really, this is the core of doing science. We didn’t quite have the initial, immediate take and we kept trying to have conversations about “it” in the lab and we just couldn’t really talk about it. And I felt like, okay we see things really differently. So we just really need to talk about this subject, but all of my colleagues didn’t want conflict. And I didn’t really see it as conflict, I saw it as, oh I we have different perspectives, so we should talk about this and really understand what these differences are. But they viewed it as conflict so they avoided the conversation. Which is incredibly frustrating for me because I felt like every time we would get to the meat of the problem, they would just duck out of the conversation in one way or another because they didn’t want to have a different conversation. To me, if we can’t have a difficult conversation, which really isn’t a difficult conversation, then we really can’t get anything done. We literally can’t do the science.

And some of that fear of conflict comes the insecurity of the relationship. When the other means well and likes and respects you, then you’re not afraid to disagree with them because you know its not going to damage the relationship. And there were really no personal issues at all.

RR: yeah, its cultural

YL: yeah, and it really affected my ability to …well, it stymied me from having meaningful collaboration

RR: Okay, for the sake of this diversity conversation, let’s step back a little bit. Let’s say okay, I know you identify yourself as Latina correct?

YL: yes

RR: A lot of these things, would you say it was because they knew you were Latina and a majority of that work environment was not?

YL: No, I don’t think it was that explicit because I am very “white” and white people perceive me as being very white. And Latino people understand that Latinos are of all races, especially in the US with lots of white Latinos. But white people don’t get that. And I remember a conversation with one of my colleagues. I said something in Spanish and he responded in surprise. Saying, “Oh I didn’t know you speak Spanish!” And I laughed and said, what do you mean, you don't know how to speak Spanish? So it was a level of obliviousness to that whole thing…an explicit obliviousness. But there were differences rooted in culture, it’s just that who I am and how I approach the world is rooted in that culture and it put me at a difference. But we didn’t even have that foundation of them understanding me. And I don’t know what they would have done with that information anyway, but they didn’t view me that way.

RR: Wow, it seemed like they didn’t have that much exposure to other cultures.

YL: And that’s the whole thing about it. You’re dealing with a flip culture of people who have an extremely low exposure to cultural heterogeneity of any kind. And that’s very different from the world that I grew up in where there’s extremely high diversity. I grew up in Oakland, one of the most diverse places in the world. And that diversity is very front and center and you have to deal with it. It really influences this issue of how do you deal with conflict? How do you deal with a difference in opinions? How do you think about it, feel about it, and how to take care of relationships when people are different from you? This is the point that I could just NOT get past; my whole approach to things is the right approach if you want to sustain diversity. It’s not that it’s just my approach; it’s the better approach for that purpose. But they weren’t comfortable with it because it was unfamiliar. They were much more about, “let’s not rock the boat, let’s all go along, get along”. That was extremely conflicting at first, it was stuff that I didn’t know was going to be a conflict; that they would be avoiding the conflict and not appreciating the way that it was stunting the environment.

RR: So it was kind of your driving force to switch careers?

YL: No, it was definitely my driving force. It was something that I couldn’t get past.

RR: Do you think that’s a common thing in the Modeler’s world of science?

YL: I think that in the modeling part of the world, it’s a very small world. There are not a lot of people in it. There’s also this weird thing where there’s no undergraduate program (or at least there wasn’t, but maybe there is now). People who are my age all came to modeling a different way.

There’s a couple of dynamics there; people came to their methodical skill sets from totally different instances. Some people studied mathematics or statistics, learned in between, some were computer engineers. So everyone has a different disciplinary training and there’s a lack of some common disciplinary vocabulary. Everyone has their own way of doing things. It’s not like we all studied the same way, have the same textbooks, major, or solve the same problems. We don’t have the same mathematical vocabulary.

The other thing is that there are a lot of people, especially in Ecology, who didn’t get the full rigorous mathematical training. So there’s this certain insecurity that they bring to their knowledge of mathematics. And I know that for myself it’s a combination of getting rigorous training and I found self-confidence as a limitation. It was a really recurring issue where I had to be very sensitive to the sense that people might clam up because they were going to think that they weren’t good enough at math. So that’s dealing with people my age and younger.

People older are an even smaller population of people, because Ecology is getting more mathematical over time. People have been doing it for a long time, there’s just not very many of them. And they are pretty much, universally, white men. I don’t know…there are some middle rank women, not many. None of them are senior rank.

So that dynamic was different and in many ways a lot easier than what I had with my peers. The dynamic I had to appreciate going in, is that people would look at me as sort of a young woman and just assume that I didn’t know my math. Any time I talked to them I had to sort of prove and establish my reputation and knowing my stuff. And I certainly learned how to deal with that. And I found people to be pretty open and persuadable.

RR: So would you say that throughout your career, you’ve seen or worked with other people of color or has it really just been a non-diverse experience?

YL: It’s definitely been non-diverse. I’ve worked with students that I’ve advised, but no, not really. I’ve worked with women, but no people of color.

And I’m working in a domain that has several overlapping reasons why there are no people of color. It’s the math, fisheries and natural resources, ecology, and science. There are several cross sections that might eliminate people of color being in there.

RR: Being in the research realm with a statistician as an advisor, I don’t connect to the way he thinks or advises. He comes from the old boys club of Ecologists; old white men. It kind of makes me wonder, in the world of Modelers and Statisticians in environmental professions, what will that be like for the future where the rest of the world is going to diversify? Is there going to be opportunity or even this openness to different perspectives in Modeling to allow these kids growing up in a diverse world to succeed?

YL: There is extremely low level of awareness on the subject. I don’t even think its really centralized in those terms. Modeling sub-disciplines, I would say, hasn’t reached a level of consciousness as being a problem.

The thing about the modeling side, it’s functioned as a distinct discipline up until recently. But I think as years go on, more and more it’ll be less of a subfield of Ecology. All Ecologists are doing modeling to various degrees and some are going to be full on specialists at it, but everybody will have to use modeling. You’re not going to be able to be an Ecologist without using modeling even as a commercial ecologist. In particular, it’s extremely important in the decision-making within government, in the decision making frameworks of things. So the people who are setting those policies, a lot of those are driven by mathematics and models and it’s very morphed over time. So if you want to have access to the way the decision-making is done, you have to have that tool kit under your belt..

I think the real problem that Ecology has is that the people who have the talent to do all that, aren’t going to do that there [in Ecology]. They’re going to go somewhere more lucrative and I don’t foresee any dynamic changing that in the near future.

RR: Well, just being around some of that, I totally commend you for reaching the heights you did in your career and sticking it through some of those grueling years. One of the things I struggle with too is that a lot of those things that we were feeling, whether being doubtful or fitting in, those kind of things were not really valued as meaningful conversations to have. Especially race or economic disparities that may impact our success. There are connections between my literacy of English and math to my upbringing and my culture. So I just started to assume and expect, that if I were to ever bring up those feelings influencing my ability to “finish the lab”, I might as well be speaking to a deer in headlights. They just wouldn’t get that that was a concern. You are expected to do this work and do it well and do it in this very sterile and process-driven way. But I felt like, okay but I’m human too and I have feelings towards this and because of that I have a difficult time working in study groups with you and that is going to affect my grades. And its hard to dissect that too because, what do we do now? Where do we go and is there going to be a space for that conversation as we are pulling through our careers day-to-day.

So, I don’t want to bring up any of those painful experiences or feelings for you and that decision to leave, but if there were resources that would allow you to stay in that profession what would they be?

YL: Well, I wish that I had given up sooner. I banged my head on some walls for a long, long time before I concluded I wasn’t going to knock them down. And that was painful. Why did I do that? It’s hard to know when you’re done with something. You have to respect your own process and time to go through all of that. But the things that would have really changed the experience well,... it comes down to community. If I had had a stronger professional community, we could have overcome. But in the end I felt that I was ultimately alone in my mission and the way I was trying to tackle my work in a way that just wasn’t going to be okay. It happened by accident to be in a really incompatible dynamic with people.

To be fair, in grad school we complain about our advisors not being great advisors, but what I learned in grad school is that great advisors are the exception to the rule. The vast majority of people are not being set up for long-term great careers because the advisors are not giving them that kind of support. And it’s the minority of people that are getting that support. They’re getting connected to the community, hitting great projects that give them high public profile, etc…That happens and that’s the pathway to success but there’s a lot of happy accidents that make that happen. The people who make great advisors are often not the same people who are great scientists. There’s some overlap, but there’s an awful lot of scientists that are not the greatest advisors.

RR: That’s the other thing I noticed, the way students are coming into these programs… we are students. And scientists are not obligated to learn how to teach. They know how to disseminate information. And a lot of the time, students are looking for that process of learning and understanding of the content. In the science/research realm, it’s very much that process of the scientific method and getting that information, but teaching is a different thing too. So why aren’t graduate students taking classes in curriculum development or pedagogy? That’s missing!

YL: Yes, and so I did take a class in graduate school in pedagogy. And my advisors weren’t supportive. It definitely wasn’t viewed as the core of what I was doing.

Walking away from my research and revising my resume for a non-research environment, I was amazed to find out that one of the things on my resume that stands out to people and always gets comments is my teaching! I did these workshops for my sanity’s sake, just so I had something to do. And it was never really supported by anyone, ever. And that was the thing that was the most marketable point on my resume now. But in research, everything that’s not contributed to first author publications is viewed as the enemy of first author publications. It’s taking time away from what you’re supposed to be doing.

RR: It’s that publish or perish culture.

YL: And yeah those are the things that happen. But one of the things that is a problem, particularly for students of color, is there are multiple reasons why you are at a disconnect with your advisor. There’s a tendency to think that, “oh, it’s me, its because I’m just not getting things”, “I have to learn how to go with the flow more…you know, internalize.” Instead of realizing, oh this person is doing a really bad job explaining this to me and I should find someone who can do a better job. And one thing to know about graduate school is that one person is not a committee. You need more than one person on your team; there’s no perfect individual. And hopefully you can get a team together and together they’re going to make what you need. And your whole key to success is assembling that team that can actually support you in all the dimensions that you need. But in order to do that you need to get over the idea that you’re just supposed to know this stuff. And a lot of times you’re treated like, you’re just supposed to know this! And as a person of color you’re sort of used to being off some of the times and you buy it! And you catch yourself saying, oh, yeah, I’m supposed to know that!

RR: yeah, I’ve said that to myself plenty of times!

YL: There’s a lot of stuff they tell you you’re supposed to know…It’s not you!

I guess the one thing I would add is that for many years I thought this was what I was going to do. I was going to get the big “R1 Research Professorship” and I was going to be a professor. So I finally get to writing the application, they’re very long and complicated. And I spent exactly one season officially on the job market and maybe sent out 4 copies of the same application. And that process of putting that all together I realized, “Oh, wait a minute, I totally don’t want to do this!”

And in particular there was a job I was invited to apply for, it was a good situation, excellent dept, good people. So on paper it was a great job. But it required me to move to Gainesville, Florida. And it occurred to me that this was the dream, this is the best-case scenario. If it’s not Gainesville, its going to be somewhere. And when you think about your life, your life is the department; this is your whole world. And you have to be okay with that. And I realized that it was just impossible for me to be okay with that. I can be okay in this field as long as I had a foot firmly in another world. But if my entire world was just this department I would be unhappy. There just wasn’t enough there.

I realized I just needed to start prioritizing geography because of that diversity thing. With whatever else was happening, being in LA vs. in Seattle, it’s just easier for me to be happy. Even if the work thing wasn’t happening the whole rest of my world just ends up being really important.

RR: That’s something to be valued as well; D Word is looking at environmental professions in general, and seeing what happens when real life drives you in different directions and that it’s totally fine. It’s an important discussion in diversity where we don’t have to feel obligated to stay if its not the right fit. You have to create those healthy boundaries and those boundaries might mean that you’re going into a different field.

Youth and students will have to hear that as well. Recent graduates, college students need to know not to put too much pressure on staying in a particular field if its not making you happy. As a person of color or coming from an unrepresented group, it’s all connected with the system that prevents us from staying in one direction (the barriers).

YL: Yes, it’s not your job to solve the world’s problems. You can make your contribution. It goes back to what I said before, like you feel like you’re throwing something away. And it’s a common and understandable to feel that way but its not necessarily true. I think your experiences go on to inform what you’ll do in unpredictable ways. You just need to make sure at every moment that you are making good decision for now. Think about this year and next, don’t think about 20 years from now. If you consistently make good decisions that keep you happy and in line with your values, you’ll end up in a good place.

To find out more about Yasmin's work you can visit her website at www.yasminlucero.net

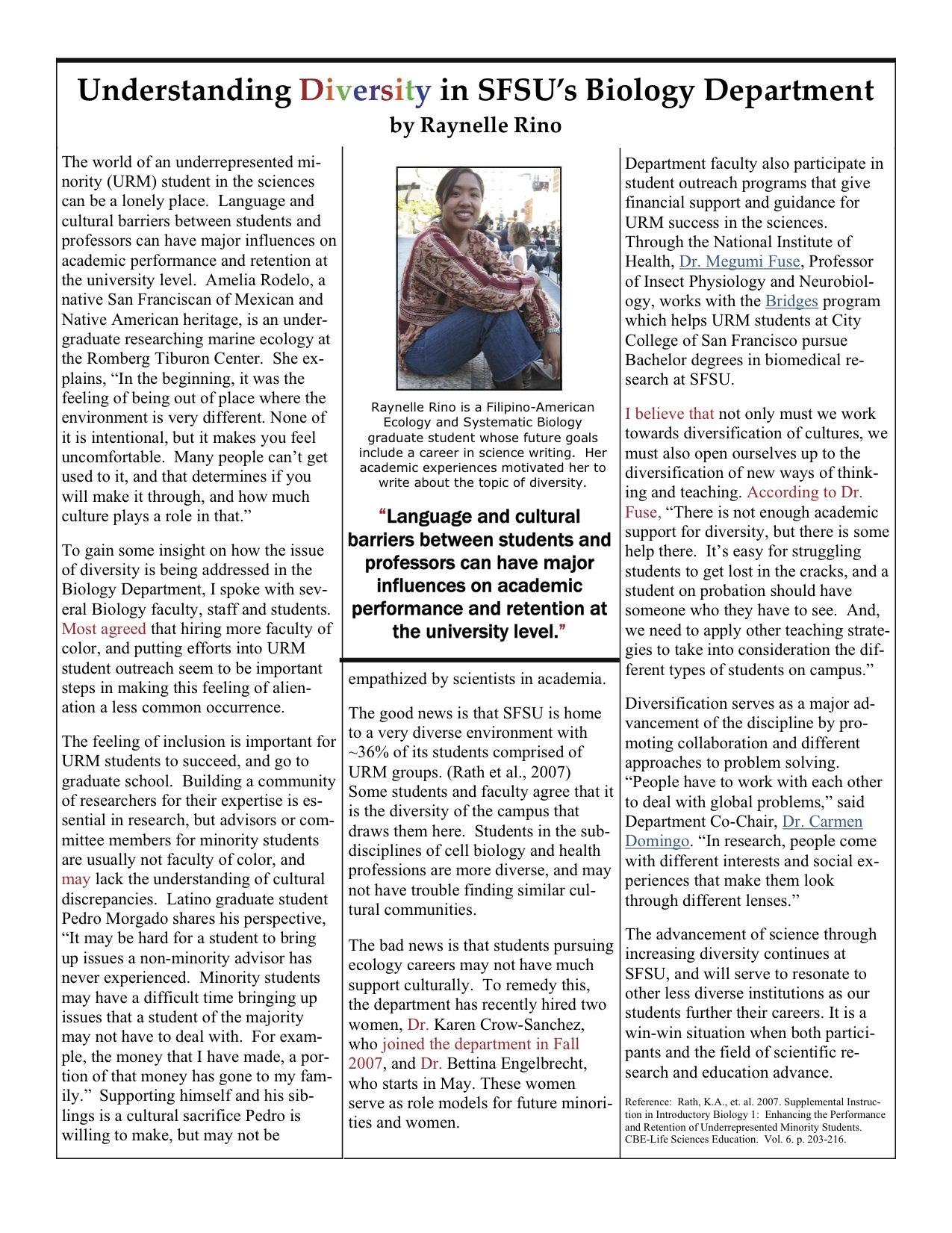

To end this year, I decided to share a piece of writing I did back when I started graduate school at San Francisco State University. I started my program in 2006. I’m still struggling to finish. In retrospect, I read back on this piece and reflected on where my life was at that point. And where I am today with respect to this conversation about diversity.

To end this year, I decided to share a piece of writing I did back when I started graduate school at San Francisco State University. I started my program in 2006. I’m still struggling to finish. In retrospect, I read back on this piece and reflected on where my life was at that point. And where I am today with respect to this conversation about diversity.